How do nations project influence? Among the various forms of national power — economic, military, and technological — diplomacy has been one of the most undercounted, and thus often overlooked, levers of influence.

In 2016, the Lowy Institute launched the Global Diplomacy Index to address this gap by mapping the world’s most significant diplomatic networks. For the first time, the Index allowed users to see the scale of a country’s official overseas presence, where connections were the thickest, and how countries’ diplomatic networks compared to each other. This provided a basis for fresh insights into the relative weight countries placed on diplomacy, and where they sought to wield it to build influence.

Eight years later, in a more contested world, diplomacy has never been a more important dimension of statecraft. The 2024 release of the Global Diplomacy Index visualises the diplomatic networks of 66 countries and territories in Asia, the Group of 20 (G20), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It now allows users to compare and explore how networks have changed over time, drawing on five public data releases. This latest iteration of the Index publishes data collected between July and November 2023.

At a macro level, diplomatic networks continue to expand and deepen — reflecting that, despite the ease of online connectivity, governments the world over continue to invest in face-to-face diplomacy and an on-the-ground presence. Great power rivalry is as prevalent in diplomacy as in other fields, with the United States and China dominating the rankings. Issues such as Russia’s war in Ukraine or economic challenges in South Africa and Argentina have also led to declines in some countries’ networks. Other countries have thinned their presence in particular regions as priorities change, while geopolitical competition has propelled the Pacific and Asia into focus.

The 2024 Global Diplomacy Index, now in its fifth iteration, is a critical resource for understanding the changing face of global diplomacy.

Superpowers neck and neck: China is ahead in Africa, East Asia, and the Pacific, while the United States has the edge in the Americas, Europe, and South Asia

China and the United States lead the world, by some margin, in the size of their diplomatic networks. Beijing tops the Index with 274 posts in its global network, followed closely by Washington with 271.

China’s rise to the top spot was rapid. In 2011, Beijing lagged behind Washington by 23 diplomatic posts. By 2019, China had surpassed the United States in having the world’s largest diplomatic network. In 2021, China pulled further ahead, leading the United States by eight posts, but by 2023, the gap narrowed again to China ahead by just three posts.

Since China assumed the lead, both countries have largely plateaued, with China down two posts overall compared to 2019 (276), and the United States fluctuating slightly to return to 2016 levels (271). This is, perhaps, to be expected. Once diplomatic networks have reached a critical mass, options for new openings reduce to second and third-tier cities, or to countries that are seen as more peripheral and often with riskier operating environments.

In that respect, it is revealing to examine the relative regional emphases of Chinese and American diplomacy to date. China has a larger diplomatic footprint than the United States in Africa (60:56), East Asia* (44:27), the Pacific Islands countries** (9:8), and Central Asia (7:6) after the United States withdrew from Afghanistan.

The United States still leads China diplomatically in Europe (78:73), North and Central America*** (40:24), and South Asia (12:10). Both countries have an equal number of posts in the Middle East (17) and South America (15).

US and Chinese regional diplomatic

footprints

Number of posts by region

China

Posts

United States US

* East Asia includes Northeast Asia (Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan), and the

11 countries of Southeast Asia. China not included for the purpose of this comparison.

** Pacific Islands countries includes the members of the Pacific Islands Forum. Australia and New

Zealand not included for the purpose of this comparison.

*** North America includes Canada and Mexico. United States not included for the purpose of this

comparison.

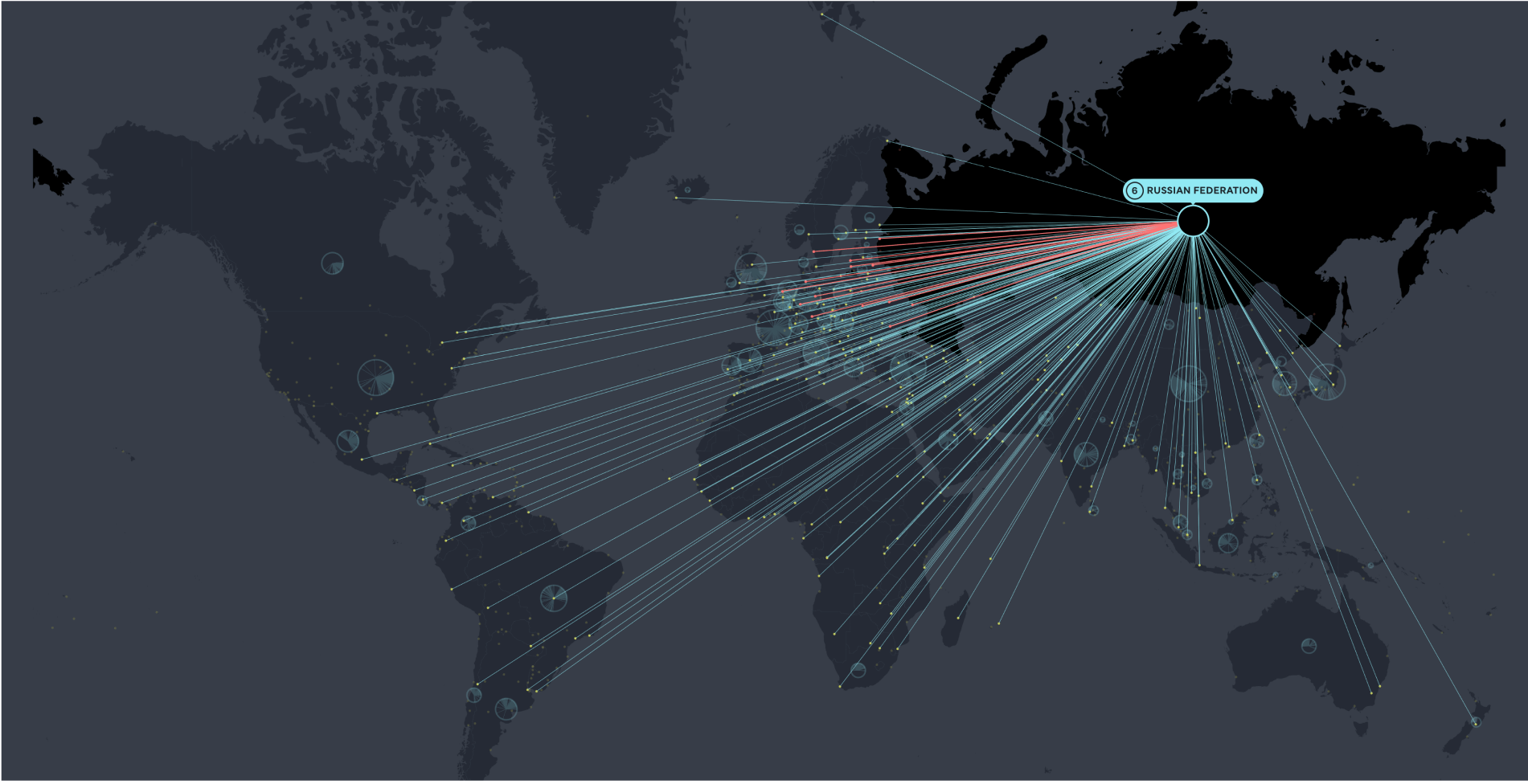

The price of war: Russia’s war in Ukraine has come at a heavy cost to its global diplomatic reach

Russia’s diplomatic connections are thinning, but still extensive

Russia’s global diplomatic network in 2023. Red lines indicate post closures following 2022 Russian

invasion of Ukraine.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has had a significant impact on its diplomatic network. Moscow has closed 14 of its posts abroad since launching its invasion in February 2022, largely as a result of deteriorating ties or diplomatic expulsions. Meanwhile, other Index countries collectively have closed 16 posts within Russia since the war began. The thinning of Russia’s diplomatic connections will impede its ability to advance its global interests.

Compounding this shrinking diplomatic network, coordinated mass expulsions of Russian diplomats across much of the Western world have severely curtailed the reach of the Kremlin’s human intelligence network. According to MI5’s Director General in November 2022, 600 Russian officials (400 of whom were suspected spies) were expelled from Europe in the wake of the invasion, striking “the most significant strategic blow” against Russia’s intelligence services in recent European history. (1)

This is not the first time Russia’s diplomatic network has been impacted by its malign actions. In 2018, the United Kingdom accused Russia of poisoning a defected Russian intelligence officer in the city of Salisbury, leading to the coordinated expulsion of more than 140 Russian diplomats from Western countries. In retaliation, Moscow expelled dozens of foreign diplomats from Russia.

Nonetheless, Moscow’s global network remains extensive — a reflection of its expansive Cold War footprint and its ongoing great power ambitions. Russia slipped from fourth on the Index in 2017 to sixth in 2021 — a rank it continues to hold today.

For Ukraine (whose diplomatic network is not included in the Index), the war has led to the closure of 11 foreign consulates within its territory (among countries included in the Index). Most foreign embassies in Kyiv have now re-opened after temporary closures at the onset of the invasion, although Australia and South Korea’s embassies in the city both remain closed.

[1] Michael Holden, “UK MI5 Chief Says Expulsion of Russian Spies has Delivered Significant Blow”, Reuters, 17 November 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/uk-mi5-chief-says-expulsion-russian-spies-has-delivered-significant-blow-2022-11-16/.

Note: The Israel–Hamas war commenced after the conclusion of our data collection period in 2023. As a result, any subsequent impact on diplomatic posts has not been reflected.

Middle powers rising: Türkiye and India have rapidly expanded their diplomatic networks in a more multipolar world

Türkiye has risen rapidly to become the third-largest diplomatic player in the world in 2023, overtaking traditional diplomatic heavyweights Japan and France. Operating 252 posts, it has steadily expanded its network, adding 24 posts since 2017 and 11 posts since the last edition of this Index in 2021. Many of Türkiye’s new posts have been in the Middle East and Africa, reflecting a diplomatic push in regions of interest to Ankara.

Overall, however, Türkiye’s network remains highly Eurocentric with 102 (40%) of its total overseas posts in that region alone, shadowing the sizeable ethnic Turkish diaspora in the Eurozone. Gaps remain in other regions. For example, with the exception of Australia and New Zealand, Türkiye is not represented in the Pacific and has a limited footprint in the Caribbean and Indian Ocean Region.

India has historically underinvested in the size of its diplomatic network relative to its demographic and economic weight, sitting just outside the top ten countries in the Global Diplomacy Index. However, together with Türkiye, India has the fastest growing network of any Index country, also adding 11 posts since 2021. Almost three-quarters of these new posts (8) are in Africa, in part reflecting India’s growing economic ties with the region and its ambition to position itself as leader of the Global South.

India’s diplomatic footprint is most pronounced in Africa, Asia, and Europe, and it is represented in every country in Asia, Eastern Africa, and the Indian Ocean Region. India has limited diplomatic representation in the Pacific, operating only two posts among the Pacific Islands Forum members (excluding Australia and New Zealand).

Several other countries have grown their networks substantially since 2021. Czechia, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Saudi Arabia each added eight new posts; Hungary and New Zealand both added seven; and Colombia and Pakistan both added six.

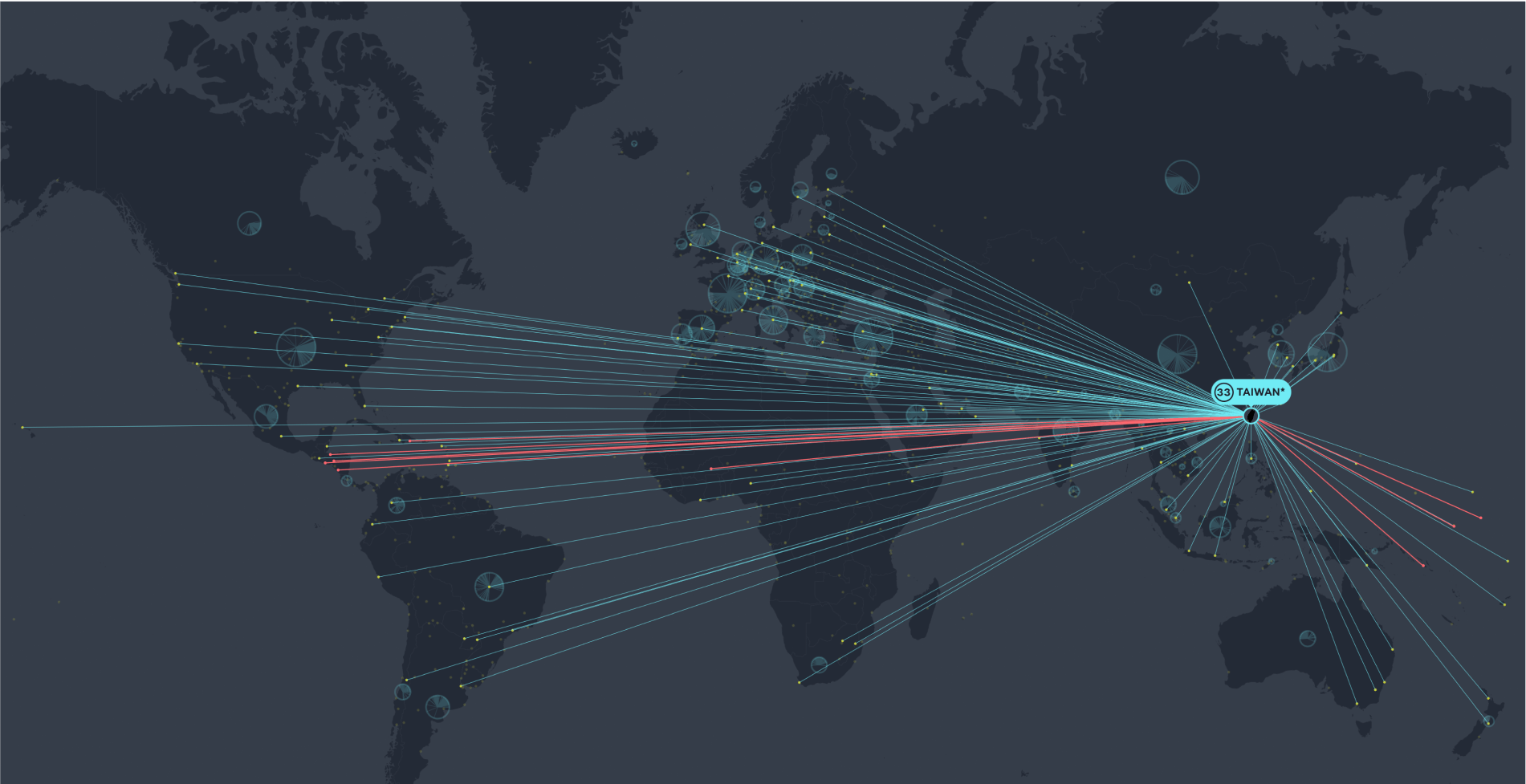

Diplomatic backsliding: Taiwan has lost ground to China on formal recognition

Taiwan currently operates 110 overseas posts worldwide, most of which are not officially accredited as diplomatic missions, placing it 33rd on the Index. Only 12 countries in the world still maintain official diplomatic relations with Taiwan as the Republic of China.

Taiwan is struggling to preserve the few formal diplomatic relationships it has left as China picks off countries through economic and other enticements. In January 2024, Nauru became the latest country to switch its diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing, leading to the immediate closure of Taiwan’s and Nauru’s embassies to each other. Since 2017, seven other countries have also switched recognition to Beijing. At time of publishing, only 14 of Taiwan’s 110 overseas posts are officially accredited by the host country or institution — 12 embassies, one Consulate-General (in Paraguay), and one mission to the World Trade Organization, where it is recognised as a “Separate Customs Territory”.

The remaining 96 are “unofficial” trade and/or cultural offices overseas (nomenclature for these posts varies by location), serving similar functions to embassies or consulates. While not accorded diplomatic status by their hosts, these presences still allow Taiwan to advocate its interests and provide services to Taiwanese people overseas. Since 2017, this figure has increased by seven, reflecting the importance Taiwan places on international outreach and engagement, despite its increasing official isolation.

Taiwan is losing formal diplomatic partners, but maintains an expansive network of mostly

unofficial posts

Red lines indicate post closures since 2017

Hosts with the most: European cities top the list of the busiest diplomatic capitals, Damascus saw the most embassy re-openings, and Kabul experienced the greatest number of closures

Diplomatic influence is not only enabled by a country’s presence abroad, but also by its ability to attract and host foreign missions at home.

At a city level, Europe dominates with four out of five of the most popular diplomatic capitals in the world for those included in the Index. The presence of large multilateral institutions exerts a strong gravitational pull for the top five host cities, with Brussels (host to 124 foreign missions) the base for both the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO); Paris (118 posts) hosting the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); New York (116) hosting the United Nations Headquarters; Geneva (99) hosting the World Trade Organization (WTO) and a number of UN specialised agencies; and Vienna (98) similarly hosting a number of UN bodies as well as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Jakarta hosts the sixth-largest number of foreign posts (75) from countries on the Index, including 20 standalone missions to Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states. However, the number of posts does not tell the whole story. For example, Jakarta is the largest post in Australia’s global diplomatic network by number of staff, reflecting the importance of Indonesia and ASEAN to Australia’s foreign policy.

Damascus is the city that saw the largest resurgence in diplomatic missions (six new posts since 2017) as several countries re-opened official channels with the Assad regime, while Kabul saw the largest decline (19 post closures), prompted by the United States’ withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Taliban takeover in 2021. Khartoum experienced the next-highest number of closures (14) over the last five years as conflict raged in Sudan, while Pyongyang saw ten closures, reflecting North Korea’s deepening isolation.

At a country level, the United States remains the locus of global diplomatic activity, hosting some 461 foreign posts (including 75 permanent missions to international organisations), belonging to countries included in the Index. China, hosting 271 foreign posts, is a distant second.

When taking into account all countries (not just the 66 included in the Index), Beijing and Washington are the lead host cities.

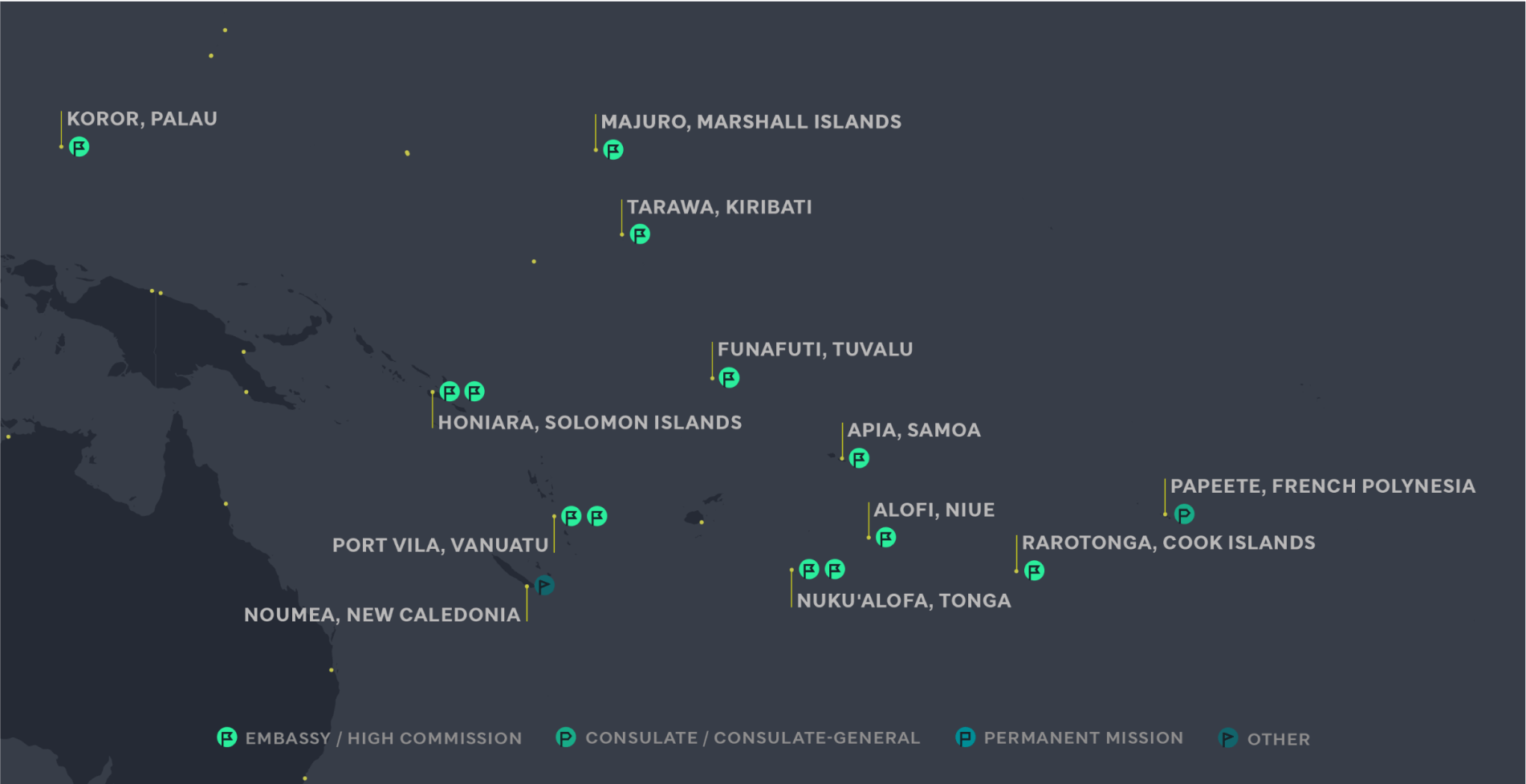

A rush to the Pacific: Geopolitical competition has driven a surge of new diplomatic missions in Pacific Islands countries

Since 2017, the South Pacific, including Australia and New Zealand, has experienced the fastest growth rate of any region in the world in terms of hosting new foreign diplomatic posts — expanding by almost ten per cent (29 new posts), albeit from a low base. Roughly half of these posts (14) were in Australia and New Zealand. But the uptick in diplomatic attention also reflects rising competition for influence in the smaller, strategically positioned Pacific Islands states, which saw the opening of 15 new posts, including from Australia, China, Europe, and the United States.

As part of its strategic re-engagement with the Pacific, the United States is growing its diplomatic footprint in the region. The United States has re-opened an embassy in Solomon Islands and opened a new one in Tonga. It has also announced its intention to open at least two more missions in Vanuatu and Kiribati. If realised, this would bring the US network in the Pacific Islands (excluding Australia and New Zealand) from eight posts at present to ten.

Meanwhile, China has been growing its footprint in the region, too. It has added an embassy in Solomon Islands and upgraded its unofficial presence in Kiribati to an embassy, reflecting those countries’ switch in diplomatic recognition away from Taipei. Beijing is expected to establish an embassy in Nauru, following the latter’s switch in diplomatic recognition to China in January 2024. Doing so would also bring its total count in the Pacific Islands to ten.

While the Pacific grew the fastest in relative terms, Europe (+117) is the region that saw the greatest absolute number of new foreign diplomatic posts opened since 2017. Europe also maintains the highest concentration of diplomatic missions in the Index. By contrast, South America grew the slowest of any region in the world, adding just three foreign diplomatic posts on the Index.

Growing diplomatic interest in the Pacific New posts opened 2017-2023

Asia in focus: Japan is a global diplomatic heavyweight, while Indonesia leads for its diplomatic network among Southeast Asian countries

Japan’s growing military budget has attracted much global attention. But Japan also operates one of the largest diplomatic networks in the world (ranked fourth overall with a total of 251 posts) and, after China, has the largest global diplomatic network of any Asian country. Japan has expanded its network incrementally, by 11 posts since 2017.

Indonesia, the third-largest democracy in the world and the country with the largest Muslim population, holds the most extensive global diplomatic network of any Southeast Asian country, operating 130 overseas missions abroad (ranked 23rd on the Index). However, its overall network has declined marginally by three posts since 2017. Indonesia’s network is concentrated in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East, with limited representation in Latin America and Africa. Indonesia is followed in the region by Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam in terms of overall size of networks.

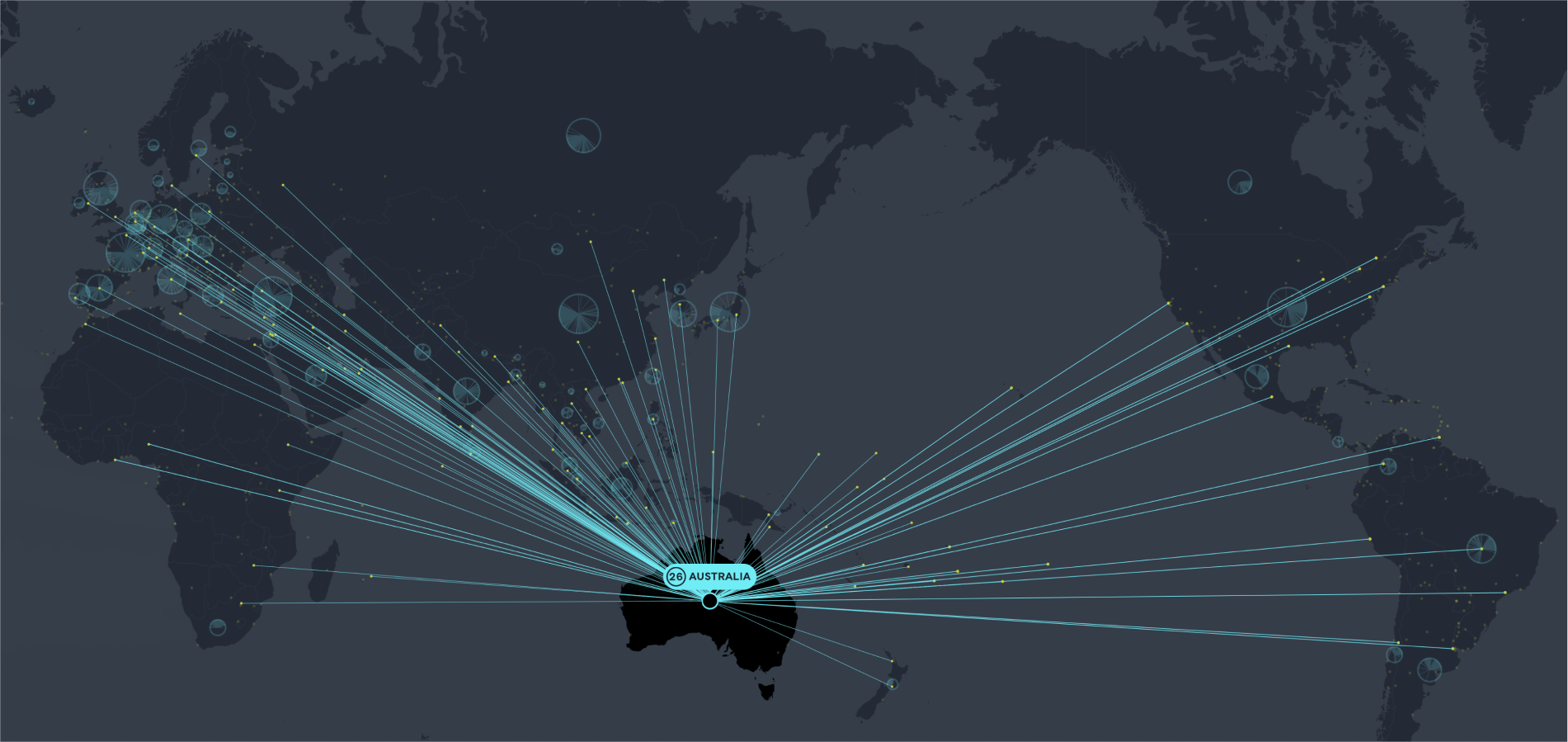

Australia: Near the bottom of the G20 but leading the charge in the South Pacific

Australia’s diplomatic footprint, ranked 26th on the overall Index, remains undersized relative to its economic weight as the fourteenth-largest economy in the world and status as a high-income middle power. With 124 posts, the size of Australia’s global diplomatic network is near the bottom of the G20, ahead of only South Africa, which closed nine posts during the pandemic, citing fiscal constraints.

Australia’s network is concentrated in Asia (38 posts), with a particular focus on Southeast Asia (17), followed by Europe (30) and the Pacific Islands (17). Canberra has expanded its presence most rapidly in the South Pacific, opening six missions in the Pacific Islands since 2017. Australia now has official representation in every Pacific Islands Forum member country.

Australia maintains a limited diplomatic footprint in Africa (9), South America (6), and the Caribbean (1). It has no resident posts in Central Africa, Central America, Central Asia, the Baltic region, or the Caucasus.

Australia’s global diplomatic network, 2023

Published by Lowy Institute, 31 Bligh Street Sydney NSW 2000 Copyright © Lowy Institute 2024 Project lead: Ryan Neelam. Principal researchers: Ryan Neelam, Jack Sato. Acknowledgements: Review, editorial, and design contributions of Hervé Lemahieu, Clare Caldwell, Ian Bruce, Stephen Hutchings, Meg Keen. Interactive website designed and produced by Glider. The researchers are grateful to the relevant ministries of foreign affairs, together with their embassies and consulates accredited to Australia, for the feedback and assistance provided in the data collection process. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Lowy Institute © 2024 Platform + Design by Glider